1931

After thousands of miles, the flight around the world for Clyde Pangborn (born 1896) and Hugh Herndon (born 1899) ended directly in prison: The two American aviators were arrested in Japan, charged with flying over military territory and taking pictures. After paying fines of $1000 each, they were released and permitted to take off, but they were allowed only one attempt. From a beach 300 miles (482 kilometers) away from Tokyo, they soared into the air on 4th October 1931.

Upon take-off, their red Bellanca Skyrocket, baptized “Miss Veedol”, was seriously overloaded, carrying 915 gallons (3464 liters) of gasoline. This made the aircraft much heavier than the manufacturer had ever allowed. Not only did Pangborn install more gasoline tanks, he also modified the landing gear in such a way that it could be released in the air.

Upon take-off, their red Bellanca Skyrocket, baptized “Miss Veedol”, was seriously overloaded, carrying 915 gallons (3464 liters) of gasoline. This made the aircraft much heavier than the manufacturer had ever allowed. Not only did Pangborn install more gasoline tanks, he also modified the landing gear in such a way that it could be released in the air.

The former military pilot calculated that dropping the landing gear would decrease the aerodynamic drag and fuel consumption, but increase the speed of “Miss Veedol”.

Three hours into the flight, Pangborn dropped the wheels, but two struts of the landing gear held and would not be shaken loose. “Upside-Down Pangborn”, as he was called in his early days as an aerial acrobat, had to crawl out on the wing at 14,000 ft (4,262km) above the icy waters of the Pacific. He had to do this barefoot, because he left his shoes back in Japan for the sake of less weight. After 20 minutes of daring toil, he was able to remove the struts. Pangborn’s experience (he spent 17,000 hours in the air) made the difference between success and a crash.

Three hours into the flight, Pangborn dropped the wheels, but two struts of the landing gear held and would not be shaken loose. “Upside-Down Pangborn”, as he was called in his early days as an aerial acrobat, had to crawl out on the wing at 14,000 ft (4,262km) above the icy waters of the Pacific. He had to do this barefoot, because he left his shoes back in Japan for the sake of less weight. After 20 minutes of daring toil, he was able to remove the struts. Pangborn’s experience (he spent 17,000 hours in the air) made the difference between success and a crash.

Hugh Herndon (left) and Clyde Pangborn (right) arriving in Wenatchee on 5th October 1931.

Other troubles were ahead. Co-pilot Hugh Herndon, financier of the adventure, forgot to pump fuel from the fuselage tanks to the wing tanks, which turned off the engine. “Pang” had to dive the airplane from cruising altitude and pulled out at 1,400 ft (430m), to get the engine started again. After they had fought the bitter cold over the Gulf of Alaska, dense fog obscured possible landing sites and fuel was running low after more than 40 hours in the air, as their reliable LONGINES watches indicated.

Pangborn decided to try for Wenatchee, an area he was familiar with from his childhood. He skillful landed the big red Bellanca on its belly, after 41 hours and 13 minutes in the air. Herndon suffered a slight bump to his head, as Miss Veedol had at her belly and propeller.

Pangborn decided to try for Wenatchee, an area he was familiar with from his childhood. He skillful landed the big red Bellanca on its belly, after 41 hours and 13 minutes in the air. Herndon suffered a slight bump to his head, as Miss Veedol had at her belly and propeller.

Pangborn and Herndon succeeded in making the longest non-stop flight to date, over a distance of nearly 8851 km (5500 miles). They were awarded a prize of $25,000 $ by a Japanese newspaper for completing the first non-stop flight from Japan to the United States.

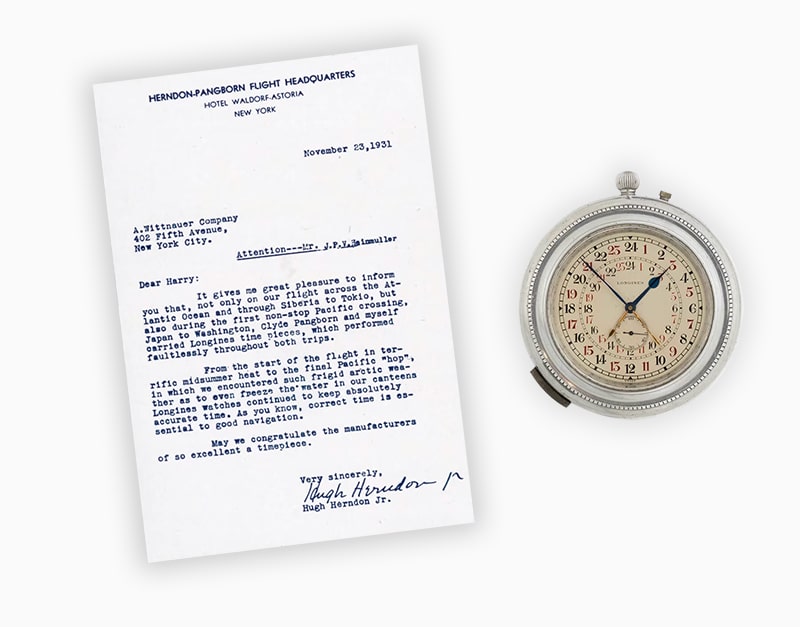

Herndon wrote to LONGINES-Wittnauer that during the Atlantic and the first Pacific crossing, “Clyde Pangborn and myself carried LONGINES timepieces, which performed faultlessly throughout both trips.” During the final Pacific flight, “in which we encountered such frigid arctic weather as to even freeze the water in our canteens LONGINES watches continued to keep absolutely accurate time,” explained Herndon in November 1931, and added: “As you know, correct time is essential to good navigation.”

Herndon wrote to LONGINES-Wittnauer that during the Atlantic and the first Pacific crossing, “Clyde Pangborn and myself carried LONGINES timepieces, which performed faultlessly throughout both trips.” During the final Pacific flight, “in which we encountered such frigid arctic weather as to even freeze the water in our canteens LONGINES watches continued to keep absolutely accurate time,” explained Herndon in November 1931, and added: “As you know, correct time is essential to good navigation.”

“...we encountered such frigid arctic weather as to even freeze the water in our canteens LONGINES watches continued to keep absolutely accurate time. As you know, correct time is essential to good navigation. May we congratulate the manufacturers of so excellent a timepiece.”

LONGINES Cockpit Clock with Double Time Zones (1931)

Furnished to Aviators Clyde Pangborn and Hugh Herndon.

Double minute- and hour-hands to indicate an independent second timezone. Two concentric 24-hour dials and small seconds. Additional pusher to stop the movement, enabling to synchronize the watch to the second with a radio time signal.

Double minute- and hour-hands to indicate an independent second timezone. Two concentric 24-hour dials and small seconds. Additional pusher to stop the movement, enabling to synchronize the watch to the second with a radio time signal.

Case made of aluminum, typical for aviation clocks. Movement cal. 18.69N, Breguet overcoil, bimetallic balance, movement engraved “patented 6 March 1911”, referring to the patent of LONGINES (No 52579) for watches with double minute- and hour-hands, developed for Turkey («Montre turque à deux tours d’heures»).

LONGINES Cockpit Clock Credit ©Oliver Hartmann

Letter sent from Hugh Herndon and Clyde Pangborn to LONGINES in 1931.