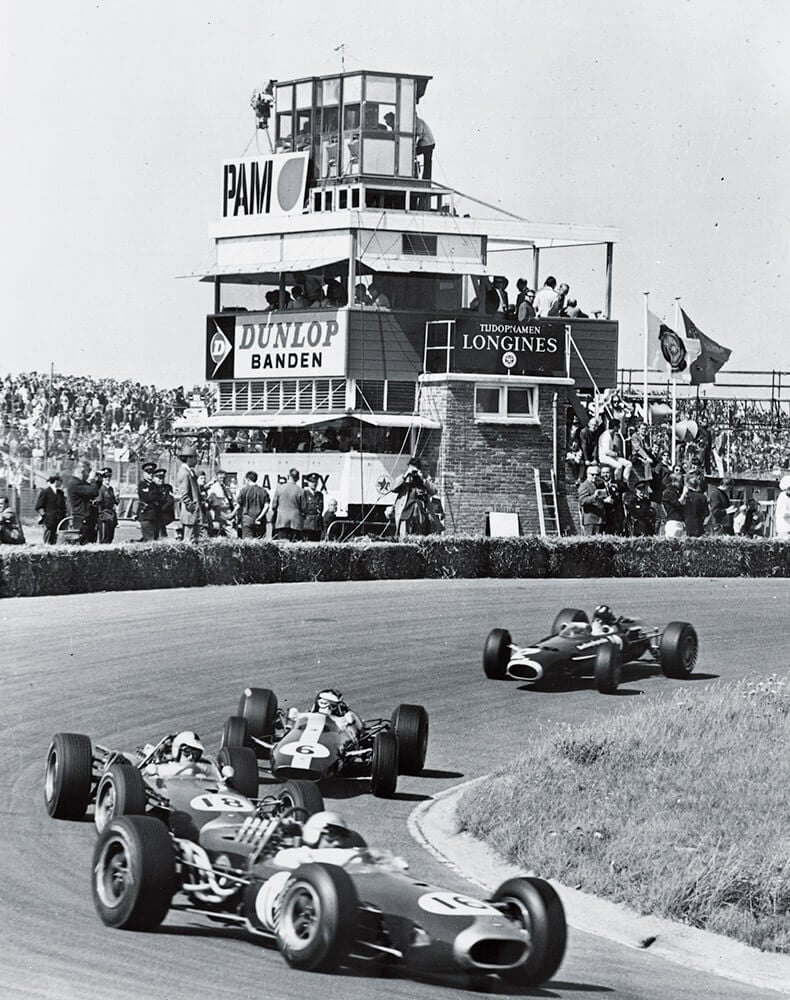

Dutch Grand Prix 1966: Winner Jack Brabham (AUS) in his Brabham-Repco leads team-mate Denny Hulme (NZ).

1933-1992

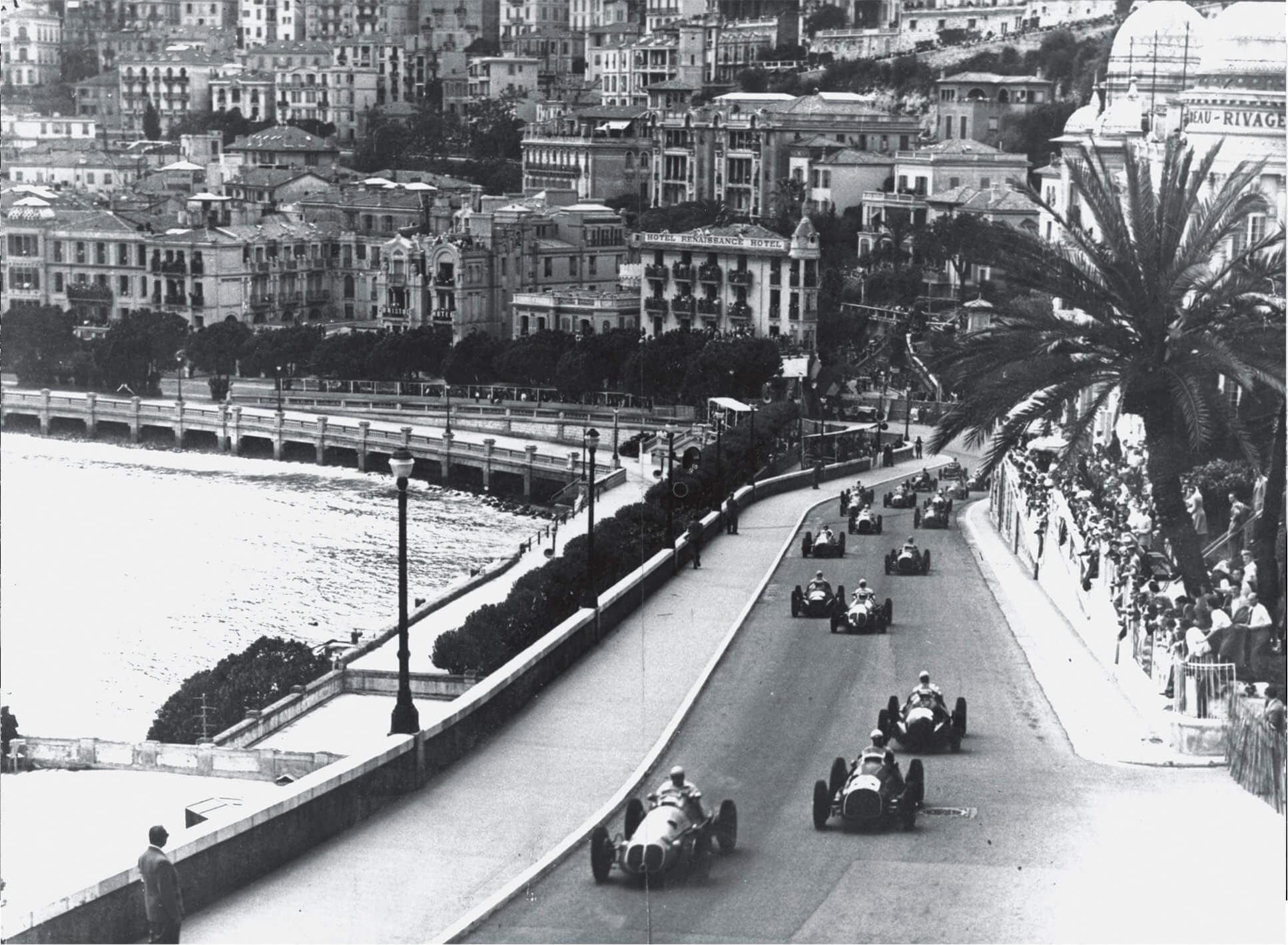

LONGINES has a rich history when it comes to motorsports, appointed Official Timekeeper for thousands of events. The first race LONGINES timed was the Grand Prix of Brasilia, in as early as 1933, when Formula One had not yet come into existence.

At the inaugural season of Formula One in 1950, LONGINES timed the famous Grand Prix de Monaco and acted as Timekeeper for the 500 miles of Indianapolis in the USA. In the 1950s, the Saint-Imier-based brand timed Formula One races in Barcelona (Spain), Bern (Switzerland), Buenos Aires (Argentina), Zandvoort (Netherlands), Spa-Francorchamps (Belgium) and Melbourne (Australia), as well as numerous other racing events and hill climbs.

At the inaugural season of Formula One in 1950, LONGINES timed the famous Grand Prix de Monaco and acted as Timekeeper for the 500 miles of Indianapolis in the USA. In the 1950s, the Saint-Imier-based brand timed Formula One races in Barcelona (Spain), Bern (Switzerland), Buenos Aires (Argentina), Zandvoort (Netherlands), Spa-Francorchamps (Belgium) and Melbourne (Australia), as well as numerous other racing events and hill climbs.

To improve the precision and accuracy of its timekeeping, LONGINES developed a new timing system known as the Chronocaméra, which provided photographed times. The fully automatic camera recorded the order of starts and finishes, the hour, the minute, the second and the hundredth of a second. This timing system, composed of a wire cutter, radios and photocells, was officially adopted by the International Automobile Federation in October 1950.

Grand Prix F1 Belgium 1967: Graham Hill (UK) in a Lotus 49.

In 1953, LONGINES proposed Chronocinégines, the first timing device to use a quartz clock. This instrument, precise to the 100th of a second, was the first portable system to achieve absolute precision at the Neuchâtel observatory. By 1956, LONGINES had developed Chronotypogines, which used a sensor to automatically start and stop time. This instrument had the advantage of being small, robust and easy to handle. In 1956, the International Automobile Federation officially adopted the latest LONGINES timekeeping system.

The Grand Prix de Monaco was the apex in motor racing in the 1960s, the era of British dominance in the sport. In May 1963, Scottish driver Jim Clark set the pole position in his Lotus 25, the first modern monocoque car that was subsequently copied by all the other teams. In the qualifying session, LONGINES timed 1 minute and 34.3 seconds for Clark, 0.7 seconds faster than Graham Hill from England in his BRM.

The Grand Prix de Monaco was the apex in motor racing in the 1960s, the era of British dominance in the sport. In May 1963, Scottish driver Jim Clark set the pole position in his Lotus 25, the first modern monocoque car that was subsequently copied by all the other teams. In the qualifying session, LONGINES timed 1 minute and 34.3 seconds for Clark, 0.7 seconds faster than Graham Hill from England in his BRM.

During most of the race, Jim Clark was comfortably in the lead, 14 seconds ahead of his competitors in the 78th lap, until the gearbox of his lightweight Lotus broke down. Drivers had to do 2,800 gearshifts over the 100 laps, which was tough on their hands and their cars. Driving was, after all, a much more physical task at the time as there were no electronics to help the driver. “The cars may be faster today, but back then it was much harder to drive. You had to be precise, you had to be consistent and you were just not allowed to make mistakes”, remembered Jackie Stewart when CNN recently asked him about racing in the 1960s. Graham Hill took the lead until the end of the race, and won in 2 hours, 41 minutes and 49.7 seconds. This was to be Hill’s first victory out of the five he would achieve by 1969. The English “gentleman” racer with his moustache and combed-back hair was the outstanding champion of Monaco. “You get everything that you meet on a public road: lamp posts, trees, nightclubs, houses, hotels, kerbs, gutters”, said Hill as he explained why Monaco was his favourite race in an interview in 1968.

Italian Grand Prix at Monza 1986: Stefan Johansson (SWE) in his Ferrari, checking time measured by LONGINES/Olivetti.

That same year, LONGINES replaced the Chronotypogines timing device with a system called Télé-LONGINES, which could measure the 1,000th of a second. Formula One was by now an extremely popular sport, drawing in millions of television viewers worldwide.

The LONGINES engineers further improved timing by measuring the time of each car independently. The new system, developed in partnership with Italian computer company Olivetti, identified the cars using radio waves, a world first. This revolutionary timing procedure was favoured by the Formula One Constructors’ Association (FOCA) and was officially introduced at the United States Grand Prix in Long Beach in March 1980. The electronic impulses transmitted by the LONGINES encoders fitted to each car sent data to the computer extremely quickly, immediately distributing the information to the teams, the media and the public. From 1982 to 1992, LONGINES was appointed Official Timekeeper for all Formula One races.

Ferrari driver Gilles Villeneuve (middle) with his wife Joann and LONGINES timekeeper Jean Campiche (left) at the Dutch Grand Prix 1981 in Zandvoort.

The first Grand Prix de Monaco, 1950.