Graham Hill (double World Formula 1 Champion and winner of the 24 Hours of Le Mans), at the start of the RAC Rally in England in November 1965 with a LONGINES stopwatch.

1950-1985

Rally drivers compete not on a closed circuit in a artificial playground, but on public roads, asphalt, gravel, snow and ice facing every weather condition. Their instrument is not a sophisticated racing car, but a saloon or sports car with only minor modifications. A typical rally course consists of a series of short (up to about 50 km/31 miles), timed “special stages” where the actual competition takes place as well as “transport stages” where the rally cars must be driven to the next competitive stage within a time limit; penalties were applied if the stage was not completed on time. The driver therefore needed the help of a talented navigator.

The first rally to start up again after World War II was the 1946 Coupe des Alpes, one of the most challenging races in the world. Drivers had to drive 4,500 km (2,796 miles) along mountain roads, climbing and descending a hundred of the highest passes in the French Alps. “The differences in altitude that follow one another at a rapid pace test even the most seasoned organism. Ears hurt”, noted French co-driver Jean-François Jacob, after a 1969 win in an Alpine A110. The race was fought in September, when rain made the roads wet and treacherous. Landslides, and sudden and unpredictable rock fall became dangerous traps in the most unexpected places. Snow proved to be an additional danger. “It falls only at very high altitudes and quickly turns into a dangerous soup that defies the best tyres. The hazards of the mechanics raise the spectre of abandonment above the bonnet of every car. The tension, the inevitable blows of fate in such a long event, (…) generate sleep and fatigue. This gives rise to wild hopes and dreams. Many disappointments are the result. But it also brings back unforgettable memories”, wrote navigator Jacob.

The first rally to start up again after World War II was the 1946 Coupe des Alpes, one of the most challenging races in the world. Drivers had to drive 4,500 km (2,796 miles) along mountain roads, climbing and descending a hundred of the highest passes in the French Alps. “The differences in altitude that follow one another at a rapid pace test even the most seasoned organism. Ears hurt”, noted French co-driver Jean-François Jacob, after a 1969 win in an Alpine A110. The race was fought in September, when rain made the roads wet and treacherous. Landslides, and sudden and unpredictable rock fall became dangerous traps in the most unexpected places. Snow proved to be an additional danger. “It falls only at very high altitudes and quickly turns into a dangerous soup that defies the best tyres. The hazards of the mechanics raise the spectre of abandonment above the bonnet of every car. The tension, the inevitable blows of fate in such a long event, (…) generate sleep and fatigue. This gives rise to wild hopes and dreams. Many disappointments are the result. But it also brings back unforgettable memories”, wrote navigator Jacob.

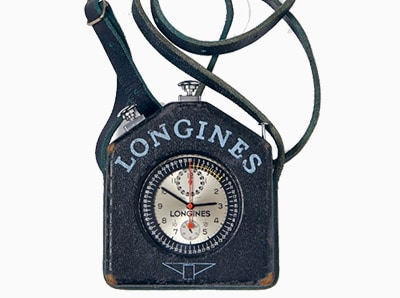

Motor racing was an enriching experience for him: “I made solid friendships, discovered respectable and loyal competitors, and also rubbed shoulders with a large number of idiots, excited and dangerous individuals whose tolerance and common sense did not exceed the thickness between their sole and a brake pedal”, summarised the winning co-driver. LONGINES timed the Coupe des Alpes, the Rallye Monte-Carlo (see next chapter), the RAC Rally of Great Britain, the TAP Rally in Portugal, the Thousand Lakes in Finland and the Rallye de Côte d’Ivoire Bandama (Ivory Coast) in Africa. To time rallies, LONGINES developed a recording device named Printogines, driven by a clock with an 8-day power reserve. Each competitor received a card which was inserted into a slot at each checkpoint. Pressing a push-button started the recording: the same indication was reproduced on a control strip that remained in the device. This paper strip enabled the organisers to establish penalties and classifications with accuracy. The timing equipment was operated outdoors and had to remain accurate even with temperature fluctuations of up to 50° C (122° F).

The Printogines instruments travelled around the world each year: from timing the Rallye Monte-Carlo and the hot Acropolis Rally in Greece to the 4,000 Miles Rally through Canada and the RAC Rally of Great Britain. “Few manufacturers have so far succeeded in building sufficiently safe, register apparatus with an accuracy at least equal to that required by the regulations”, wrote Edmond Evard, Official Timekeeper of the Automobile Club of Switzerland about LONGINES instruments. In the 1970s, after developing an electronic, highly accurate version of the Printogines, LONGINES was named Official Timekeeper for all Rallies in the World Championship Series.

The Printogines instruments travelled around the world each year: from timing the Rallye Monte-Carlo and the hot Acropolis Rally in Greece to the 4,000 Miles Rally through Canada and the RAC Rally of Great Britain. “Few manufacturers have so far succeeded in building sufficiently safe, register apparatus with an accuracy at least equal to that required by the regulations”, wrote Edmond Evard, Official Timekeeper of the Automobile Club of Switzerland about LONGINES instruments. In the 1970s, after developing an electronic, highly accurate version of the Printogines, LONGINES was named Official Timekeeper for all Rallies in the World Championship Series.

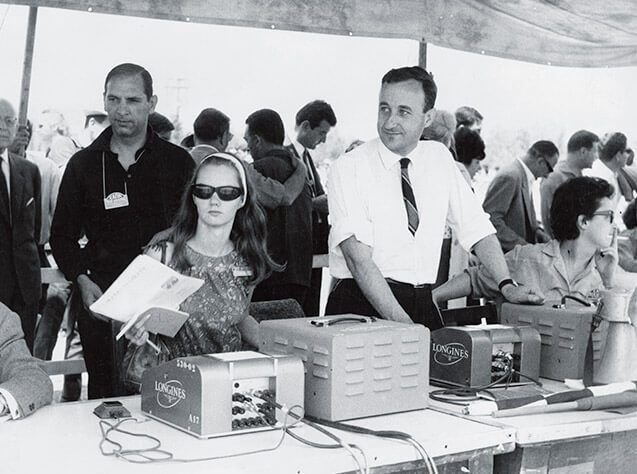

Timekeeping at Rallye Acropolis, Athens (Greece), 1965.

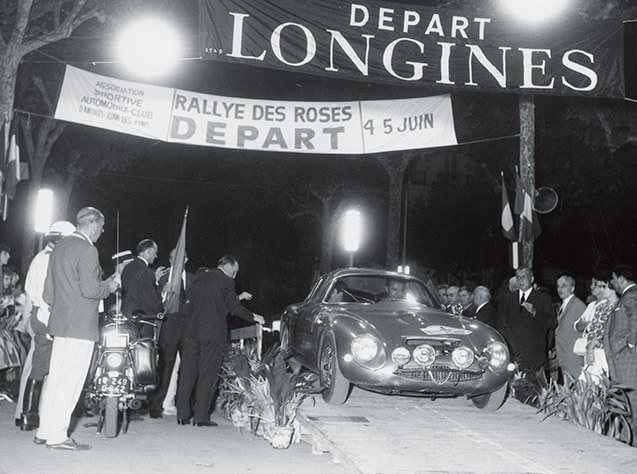

The Alfa Romeo TZ Zagato at the start of the Rallye des Roses, Antibes (France), 1966.

Winner Jean-François Jacob and Jean Vinatier in an Alpine A110 1600 at the LONGINES time control, Coupe des Alpes 1968.